While there is no single “hardest” material, the consensus among CNC machining experts points to nickel-based superalloys, with Inconel often cited as the prime example. These materials are not just hard in the traditional sense; their extreme difficulty stems from a combination of high-temperature strength, severe work-hardening tendencies, and poor thermal conductivity. This trio of challenges creates a perfect storm for rapid tool wear, low material removal rates, and a high risk of part failure during machining, demanding specialized expertise, tooling, and machinery to achieve precision results. This article explores what truly makes a material challenging to machine and breaks down the top contenders for this formidable title.

Beyond Hardness: What Truly Defines a “Difficult-to-Machine” Material?

When clients ask what the hardest material is, they’re often thinking only of surface hardness. At Hirung, our experience has shown that machinability is far more complex. Several interconnected properties determine how a material will behave under the immense pressure and heat of CNC cutting. Understanding these factors is key to successful machining strategies.

Material Hardness (Rockwell & Vickers)

Hardness is the measure of a material’s resistance to localized plastic deformation, such as scratching or indentation. Measured on scales like Rockwell or Vickers, high hardness (above 40 HRC) directly translates to greater force required to penetrate and shear the material. This puts immense stress on the cutting tool, demanding tools made from even harder materials like carbide or cubic boron nitride (CBN). Machining hardened steels, for example, is a direct battle against their sheer resistance to being cut.

Toughness and Ductility

Toughness is a material’s ability to absorb energy and deform without fracturing. While this is a desirable trait in a finished part, it creates significant challenges in machining. Tough, ductile materials don’t form clean, brittle chips that break away easily. Instead, they produce long, stringy, or “gummy” chips that can wrap around the tool and workpiece, leading to poor surface finish and potential tool breakage. These materials also require more energy to shear, contributing to heat generation.

Thermal Conductivity

This is arguably one of the most critical factors. CNC machining generates intense, localized heat at the cutting edge. In materials with good thermal conductivity like aluminum, this heat is efficiently wicked away from the tool and carried off by the chip. However, materials with low thermal conductivity, such as titanium and Inconel, act as insulators. The heat remains concentrated at the tool tip, causing it to soften, deform, and fail rapidly through a process called thermal shock. This makes heat management and coolant application absolutely critical.

Work Hardening Tendency

Some materials, most notably nickel-based superalloys and certain stainless steels, have a high tendency to work-harden. This means the very act of cutting—the pressure and heat from the tool—causes the material’s crystal structure to deform and become significantly harder in the localized area being machined. The next pass of the cutting tool then has to cut through a surface that is harder than the parent material, leading to a vicious cycle of accelerating tool wear. This phenomenon demands specific cutting strategies, like maintaining a constant chipload, to stay below the hardened layer.

The Contenders: A Breakdown of the Toughest Materials for CNC Machining

Based on the factors above, a few classes of materials consistently rise to the top of the “most difficult” list. Each presents a unique combination of challenges that push the limits of modern CNC technology.

| Material Class | Primary Challenge | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superalloys (Inconel, Hastelloy) | Extreme Work Hardening & Low Thermal Conductivity | High strength at high temps, corrosion resistance | Jet engines, gas turbines, chemical processing |

| Titanium & Alloys (Ti-6Al-4V) | Very Low Thermal Conductivity & Chemical Reactivity | High strength-to-weight ratio, biocompatibility | Aerospace components, medical implants |

| Hardened Steels (D2, AR500) | Extreme Hardness & Abrasiveness | High wear resistance, toughness | Tooling, molds, armor plating |

| Advanced Ceramics (Zirconia) | Extreme Hardness & Brittleness | Very high hardness, thermal stability | Cutting tools, medical devices, electronics |

| Composites (CFRP) | Highly Abrasive & Prone to Delamination | Very high stiffness-to-weight ratio | F1 chassis, aircraft structures, high-end sports |

Superalloys (Inconel, Hastelloy, Waspaloy): The Reigning Champions

Why are superalloys considered the hardest to machine? They maintain incredible strength even when red-hot, a property that makes them ideal for jet engine turbines but a nightmare for a cutting tool. Their combination of severe work hardening and extremely low thermal conductivity means tools wear out exceptionally fast. Cutting Inconel requires very low cutting speeds, precise depths of cut, and high-pressure coolant to stand a chance. The material’s high nickel content also makes it abrasive, further accelerating tool degradation.

Titanium and its Alloys (e.g., Ti-6Al-4V): Strong, Light, and Thermally Challenging

Titanium is prized in aerospace and medical for its fantastic strength-to-weight ratio. Its primary machining challenge is its nature as a thermal insulator. Heat does not dissipate, causing the cutting tool to become extremely hot. Furthermore, titanium is chemically reactive at high temperatures and can weld itself to the cutting tool, a phenomenon known as “galling.” This requires specialized tool coatings, sharp cutting edges to minimize friction, and a carefully managed cutting speed to prevent temperatures from reaching critical levels.

Hardened Steels (Tool Steels, D2, AR500): The Brute Force Challenge

Unlike superalloys, the challenge with hardened steels (typically 50-65 HRC) is more straightforward: they are simply incredibly hard and resistant to being cut. Machining these materials is a test of machine rigidity and tool strength. It often necessitates the use of CBN or ceramic inserts, as standard carbide tools will wear almost instantly. The process, known as hard milling or hard turning, requires powerful, stable machines and generates significant cutting forces.

Advanced Ceramics (Alumina, Zirconia): The Abrasive Adversary

While often shaped by grinding rather than conventional CNC milling, technical ceramics are among the hardest materials known. When CNC machining is required, it poses an extreme challenge. Their phenomenal hardness means diamond or PCD (polycrystalline diamond) tooling is a must. Furthermore, their brittle nature means they are highly susceptible to chipping and micro-cracks, requiring very light depths of cut and a stable, vibration-free machining process.

How Do Experts Machine These Hard Materials? The Hirung Approach

Successfully machining difficult materials isn’t about one secret trick; it’s about a holistic system of technology, strategy, and experience. At Hirung, we leverage a multi-faceted approach to turn these challenging raw materials into precision-engineered components.

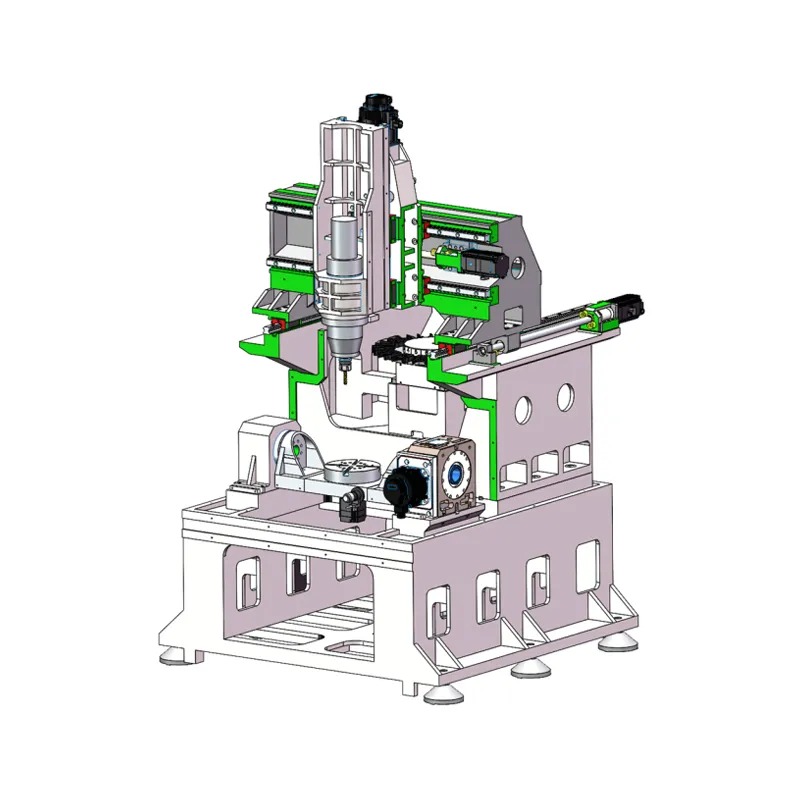

The Right Machine: Rigidity and Power are Non-Negotiable

You cannot machine hard materials effectively on a flimsy machine. The process requires a CNC machine with exceptional rigidity and damping capabilities to absorb vibration. Any chatter or vibration will be magnified at the tool tip, leading to poor surface finish and immediate tool failure. We utilize robust, high-power 5-axis machines that provide the stability and torque needed to power through tough cuts without compromising precision.

Advanced Tooling: Coatings, Geometries, and Materials

Tool selection is paramount. We use solid carbide end mills with specialized coatings like AlTiN (Aluminum Titanium Nitride) or TiSiN (Titanium Silicon Nitride) that can withstand extreme heat. The geometry of the tool—the rake angle, helix angle, and number of flutes—is carefully matched to the material. For the hardest steels and superalloys, we move to even more advanced materials like CBN (Cubic Boron Nitride), which is second only to diamond in hardness and maintains its edge at very high temperatures.

Strategic CAM Programming: The Brains of the Operation

The toolpath strategy is where experience truly shines. To combat work hardening and heat buildup, our engineers utilize advanced CAM strategies like trochoidal milling or peel milling. These toolpaths use a smaller portion of the cutting tool’s diameter but at a much deeper axial cut and higher feed rate. This ensures a consistent chip thickness, avoids shocking the tool, and uses more of the cutting edge, distributing wear and heat more effectively. Controlling tool engagement angle is critical to managing cutting forces and ensuring a stable process.

The Critical Role of Coolant and High-Pressure Systems

Coolant is not just for lubrication; its primary job in hard material machining is heat evacuation. We employ high-pressure through-spindle coolant systems (up to 1,000 psi) that blast a focused jet of fluid directly at the cutting zone. This does two things: it forcefully quenches the heat from the tool and workpiece, and it effectively blasts chips out of the cutting path, preventing them from being re-cut, which would otherwise cause catastrophic tool failure.

Why Partner with an Expert for Hard Material Machining?

Machining challenging materials like Inconel or hardened tool steel carries a high cost of failure. These raw materials are expensive, and a single mistake can lead to a scrapped part worth thousands of dollars. A broken tool, a missed tolerance, or a poor surface finish can derail an entire project. Partnering with a specialist like Hirung mitigates these risks.

Our expertise is built on years of hands-on experience. We understand the unique nuances of each material and have developed proven processes to overcome their challenges. From initial DfM (Design for Manufacturability) feedback to final inspection, our entire workflow is optimized for precision and reliability. We invest in the right technology—the machines, the software, and the tooling—so you don’t have to. This ensures your critical components are manufactured correctly, on time, and to the highest quality standards, turning a difficult manufacturing challenge into a competitive advantage for your project.

Conclusion: The Hardest Challenge is an Opportunity for Precision

So, what is the hardest material to CNC? The answer is a class of materials, led by superalloys, where multiple challenging properties converge. It’s not just about hardness, but a complex interplay of thermal conductivity, work hardening, toughness, and abrasiveness.

Overcoming these challenges isn’t just possible; it’s a testament to the power of modern manufacturing when guided by deep expertise. The ability to transform these formidable materials into an intricate turbine blade or a life-saving medical implant is what drives innovation forward. If your next project involves materials that push the boundaries of machinability, it requires a partner who sees the challenge not as a barrier, but as an opportunity to deliver unparalleled precision.

Ready to tackle your a complex project with difficult materials? Contact the experts at Hirung today, and let’s build something remarkable together.